Recent calls to 'decolonise' gallery and museum spaces mean visitors have grown used to seeing historical images featuring a Black presence as a way of opening debates on slavery, colonialism and race. So much so, that the very inclusion of a Black figure becomes a visual requisite for such discussions.

This, however, is to both ignore works that deliberately foreground whiteness as a way of alluding to colonial and imperialist histories, and to view whiteness as unburdened with racial classification.

The Royal Academy of Art's exhibition, 'Entangled Pasts, 1768–now', seeks to address both the institution's and art's role in shaping narratives around colonialism. The show features a room entitled 'Constructing Whiteness', which includes Frank Dicksee's Startled (1892).

Here, whiteness is presented as a golden Eden, inhabited by two red-haired white women, hurriedly escaping an approaching Viking long boat while struggling to conceal themselves with a white cloth.

Yet despite the title of Dicksee's work, the most startling examination of whiteness is Betye Saar's I'll Bend But I Will Not Break (1998), a work in which the white figure is conspicuous by its absence.

I'll Bend But I Will Not Break

1998, mixed media including vintage ironing board, flat iron, chain, white bedsheet, wood clothespins & rope by Betye Saar (b.1926)

Saar's assemblage consists of a starched white sheet, pegged to a washing line, embossed with the initials 'KKK'. An iron is manacled to an ironing board, the top of which is branded with a popular eighteenth-century cross-sectional print of the Brooks slave ship, showing tightly packed African figures on the Atlantic Middle Passage.

Here Saar simultaneously references the legacies of plantation enslavement, the associations of cotton with memory (a topic explored by historian Anna Arabindan-Kesson), Black women's back-breaking toil and white supremacy. The power of the piece lies in how Saar uses the white cotton sheet, an everyday object, as a stand-in for white skin. We are made 'to see' whiteness without its usual staging 'in contrast to', or 'in comparison to', something else.

Mid- to late eighteenth-century portraits of aristocratic white women reveal a similar determination 'to see' white skin. Artists used white female skin as a medium with which to produce a physical and emotional response from the viewer; it was also a way to project and deflect Britain's heightened involvement in the transatlantic slave trade and to disavow an ever-growing abolitionist movement.

It also points to the belief during this period that skin colour was a defining feature of human difference based on a racial hierarchy.

Queen Elizabeth I ('The Ditchley portrait')

c.1592

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636)

In contrast to the hard alabaster-like skin of Elizabethan portraits epitomised by The Ditchley portrait (1592) by Marcus Gheeraerts the younger, artists strove to endow white skin with a pliable quality that afforded the sitter subjectivity and gave works a sensate quality. Depicting female white skin in this way allowed artists to suggest a variety of inner virtues that were absent in dark skin because of white skin's ability to blush. The white female body, as a synonym for whiteness, came to symbolise nationhood, purity and tradition.

The eighteenth-century Irish playwright Oliver Goldsmith observed how, 'of all the colours by which mankind is diversified, it is easy to perceive that ours [white] is not only the most beautiful to the eye, but the most advantageous. The fair complexion seems…as a transparent covering to the soul: all the variations of the passions, even expressions of joy and sorrow, flows to the cheek.'

Artists of the early romantic and neoclassical periods produced portraits that present delicately rendered white skin in stark contrast to fiery cheeks. In Three Ladies Adorning a Term of Hymen (1773), Joshua Reynolds – the first president of the Royal Academy – uses the deep red cheeks and contrasting white skin of the aristocratic Montgomery sisters, Barbara, Elizabeth and Ann, to advertise their coming-of-age and fertility.

Reynolds refers to female beauty by referencing the 'Three Graces', a classic artistic trope depicting mythological figures that can be seen in Angelica Kauffman's work below. The blue-blooded whiteness of the sisters' skin is enhanced by the basket of pink roses strategically placed beside the arm of Barbara, and the serpentine of flowers held by Elizabeth – a symbol of their unbroken family lineage. The eldest sister Anne's white skin is indistinguishable from her gown.

A similar composition is employed by Reynolds in The Ladies Waldegrave (1780). The three sisters – from left to right, Maria, Laura and Horatia – are totally absorbed in their pursuits, except for Maria. Their red cheeks lend a lively quality to their skin, along with an awareness of being looked at. In turn, their cheeks, together with the crimson drapes and red ear lobes, offset varying shades and textures of white.

With powdered white hair, their translucent pale skin, which is illuminated by the satin sheen of their gowns, is accentuated by the hint of blue veins on the chest of the central figure Laura.

Reynolds applies similar degrees of detail to the women's hands. Maria's and Laura's reveal reddened knuckles and fingertips that are contrasted with the white thread and winding card. As with the Montgomery sisters, this trio is connected by aristocratic blood. Maria and Laura respectively hold and wind white silk threads, while Horatia holds a tambour, transforming the silk threads produced by her sisters into white translucent lace.

This is an appropriate activity for women of their class, and the transformation of raw silk thread into exquisite white cloth reflects the process of refinement the sisters undergo.

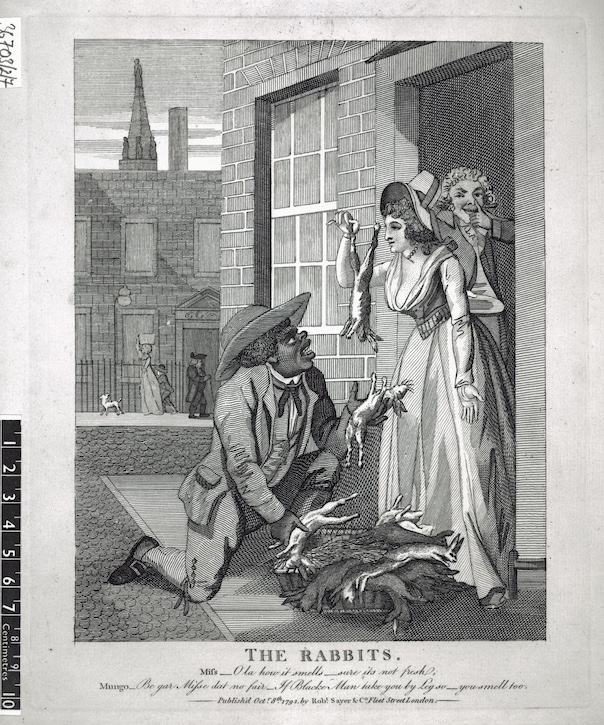

The Rabbits

1792, etching on paper by unknown maker (published in London)

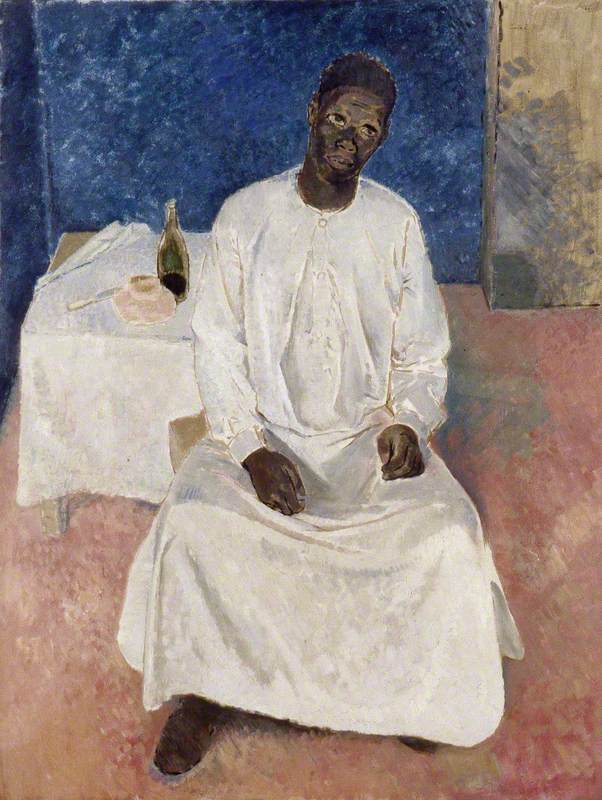

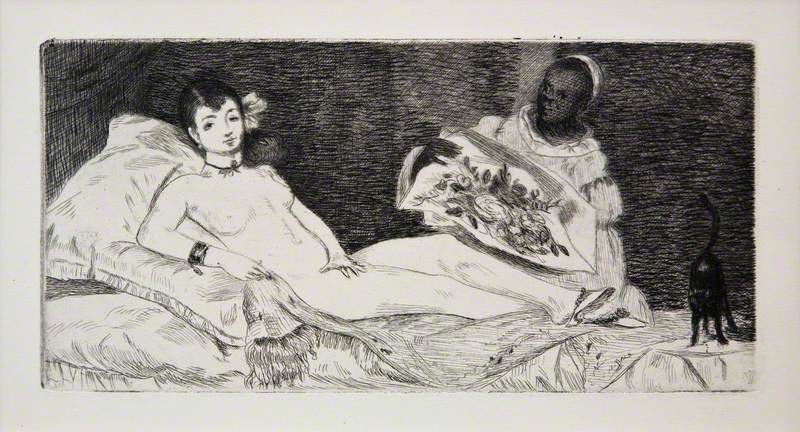

Cultural historians have noted how the abundance of British portraits that enunciate whiteness as a racial fact coincided with the abolitionist movement and concerns for interracial sex. Popular prints such as the anonymous The Rabbits (1792) and Thomas Rowlandson's Every Man Has His Hobby Horse (1784) enjoyed wide circulation.

Every Man Has His Hobby-Horse

1784, hand-coloured etching on paper by Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827)

These images, which subverted the abolitionist image of the supplicatory Black man, reflected pro-slavery sentiments publicised by individuals such as the Jamaican planter and white supremacist Edward Long: 'That the lower class of women in England, are remarkably fond of the blacks…in the course of a few generations more, the English blood will become so contaminated with this mixture…as even to reach the middle, and then the higher orders of the people, till the whole nation resembles the Portuguese and Moriscos in complexion of skin and baseness of mind.'

In Thomas Lawrence's Catherine Rebecca Gray, Lady Manners (1794), in which she is depicted as the goddess Juno (symbolised by the peacock), the fear of sullied whiteness and contaminated blood are, in my reading, suggested through the figure's delicate and frail appearance. Gray appears to float down the stone staircase.

Catherine Grey, Lady Manners

1794, oil on canvas by Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

Her illuminated chest and arms display a suffusion of blue veins and her elbows are a pale red. More discernible signs of blood-infused skin are clear in the blushing pinks of the rose held between her reddened fingertips – as well as her red cheeks, lips and nose. The need to protect her skin from the colouring rays of the sun is suggested by her pale blue gloves. Her gown is indistinguishable from her smooth, creamy skin, giving her a ghostly appearance.

According to art historian Angela Rosenthal: 'The alabaster purity of her person invites the viewer to attribute to this woman profound and pure internal virtues. This bleached body seems dematerialized, presenting whiteness visually as ethereal and threatened.'

Late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century assertions of women's natural destiny of bearing and nursing children, and the importance of familial bloodlines, become a recurring theme in other portraits by Lawrence. In Anne, Countess of Charlemont and her son James (c.1805), it is the face of the child that exhibits the fiery blush associated with aristocratic whiteness and lineage.

Anne, Countess of Charlemont, and her son James

c.1805, oil on canvas by Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

Conversely, family extraction and descent are displayed in the red-suited figure of Charles, son of Mrs Charles Thellusson, who appears rooted to, and emerging from, his mother's flowing white gown.

A number of works from this period use the gauze-like nature of lace to conjure the translucent quality of white skin, and its associations with openness and honesty. Two portraits from 1767 by Allan Ramsay, The Artist's Wife, Margaret Lindsay of Evelick and Jean Abercromby, Mrs Morison of Haddo, use soft pastel shades to give the figures' skin an organic liveliness in contrast to the consumptive frailty of Lawrence's Catherine Rebecca Gray.

The Artist's Wife, Margaret Lindsay of Evelick (c.1726–1782)

1758–1760

Allan Ramsay (1713–1784)

In both portraits, delicate nerve fibres are evoked through the transparency of the sitters' skin. Similarly, the intricate layers of lace which reveal the pink and blue gowns underneath, suggest a diaphanous skin. Both portraits also show how each sitter's skin is further racialised by their association with luxurious commodities: Margaret Lindsay by her proximity with the porcelain white urn and Jean Abercromby via the string of translucent pearls that adorns her neck.

As a form of body art, rouge, together with facial preparations designed to whiten the skin, fuelled patriarchal concerns about its ability to render white skin unreadable, masking women's true nature. Women who wore cosmetics were castigated as degenerate and barbarous. Sir Harry Beaumont, for example, compared the use of rouge by French women to the scarification of African tribesmen.

A growing cosmetic industry claimed the use of rouge – 'Circassian bloom' – would, as quoted in Neville Williams' book Powder and Paint, transform the wearer into 'the celebrated caucasus of Giorgia…the most beautiful women on earth.' Yet the contaminating and blood-altering effects of cosmetics were of concern, as many ingredients used to whiten and redden the face – such as cochineal, vermilion and powdered pearl – were foreign imports.

Rowlandson's print, Six Stages of Mending a Face, Dedicated with Respect to the Right Honble Lady Archer (1792), cruelly exposes female beauty as a fraud, aided by the chicanery of cosmetics.

Six stages of mending a face

1792, hand-coloured etching on paper by Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827)

Given such condemnation of cosmetics, François Boucher's Pompadour at Her Toilette (1750) is all the more surprising. Madame de Pompadour is seen at her toilette, holding a box of rouge in one hand and wielding a blusher brush in the other: as if in the act of painting herself, she reveals the artificiality of her white skin and blushing cheeks, so long equated with girlish refinement, modesty and purity.

More significantly, she underwrites the unstable nature of white identity by displaying its artifice and need for enhancement.

Pompadour at Her Toilette

1750, oil on canvas by François Boucher (1703–1770)

A willingness to 'see white' in portraits that on the surface appear unrelated to British colonialism serves to reframe these works in the context of current debates around race and empire. Considering these works alongside those by Black contemporary artists – such as Betye Saar – offers a more holistic understanding of the subtleties of race that promises to decentre whiteness.

Dr Janet Couloute, academic and researcher

'Entangled Pasts, 1768–now' is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London until 28th April 2024

This content was sponsored by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Anna Arabinden-Kesson, Black Bodies, White Gold: Cotton and Commerce in the Atlantic World, Duke University Press, 2021

Farah Karim-Cooper, Cosmetics in Shakespearean and Renaissance Drama, Edinburgh University Press, 2006

Kim F. Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in the Early Modern England, Cornell University Press, 1996

Caroline Palmer, 'Brazen Cheek: Face-Painters in Late Eighteenth-Century England', Oxford Art Journal, vol. 31, issue 2, June 2008

Angela Rosenthal, 'Visceral Culture: Blushing and the Legibility of Whiteness in Eighteenth-Century British Portraiture', Art History, vol. 27, issue 4, September 2004

Roxanne Wheeler, The Complexion of Race: Categories of Difference in Eighteenth-Century British Culture, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000

Neville Williams, Powder and Paint: A History of the Englishwoman's Toilet, Elizabeth I–Elizabeth II, Longman's, Green and Co., 1957

Chi-ming Yang, Performing China: Virtue, Commerce, and Orientalism in Eighteenth-Century England, 1660–1760, John Hopkins University Press, 2011